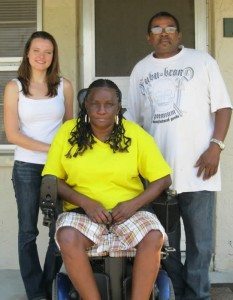

Patricia Redding, center, will soon have a long-awaited ADA-compliant unit at Norton Apartments in Clearwater, Fla., where she lives with her cousin, Nehemiah Dillard, right, who is her caregiver. With them is Stetson law student Maria Bogomaz, who assisted Gulfcoast Legal Services attorney Christine Allamanno on an affordable housing project to save the long-neglected, HUD-subsidized apartment complex and make improvements, including providing wheelchair accessible units.

Confined to a wheelchair by multiple sclerosis, Clearwater, Fla., resident Patricia Redding, 50, had become a prisoner in her own apartment when promised modifications to make it wheelchair accessible and ADA-compliant were never made.

Later, when raw sewage backed up into Redding’s unit, the property manager at Norton Apartments also failed to keep his word and replace her soaked carpet. Redding, whose cousin, Nehemiah Dillard, lives with her as her full-time, medically-necessary caregiver, saw no way out.

“I live on Social Security disability and food stamps,” said Redding.

“I was trapped in this apartment. I could not afford to move.”

What she and the 47 other low-income families living there did not know was that their landlord was preparing to file Chapter 11 bankruptcy — not only on Norton Apartments but on a total of 19 affordable multifamily housing complexes in Florida.

In 2009 and 2010, the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) gave Norton’s landlord consecutive failing scores on the condition and management of the property and required that the owner submit a plan for bringing the complex into compliance.

When the landlord didn’t respond, HUD began the process of terminating the rent subsidies and was poised to shut Norton down. Although residents had been approved for relocation assistance, much more was at stake.

“Once HUD terminates a project-based Section 8 contract, that particular housing subsidy is lost to a community’s low-income residents,” said Christine Allamanno, an attorney at Gulfcoast Legal Services in St. Petersburg, a grantee of The Florida Bar Foundation. “HUD does not put the project-based subsidy back or transfer it to another development. It is lost for good, and it is happening all over Florida at a time when we have a critical need for subsidized housing due to economic conditions.”

Allamanno is working on Florida Legal Services’ statewide Affordable Housing Project, which was funded by a $262,850 grant from the Foundation in 2010-11. In addition, Gulfcoast Legal Services received an $85,000 Foundation grant for its work on a regional affordable housing project in the Bay area together with Bay Area Legal Services, which received an additional $39,000.

As HUD was preparing to move Norton residents off the property, Allamanno and her partner on the Foundation’s regional affordable housing grant, Dorothea Lee of Bay Area Legal Services, were attending a seminar in Tampa sponsored by the Florida Housing Coalition, the National Housing Trust, and the Shimberg Center for Affordable Housing at the University of Florida. There, local and national experts in housing preservation came together to teach Florida affordable housing advocates legal and financial strategies for preserving the state’s remaining project-based Section 8 subsidies, and about the warning signs of an impending loss of such a subsidy.

“Norton met all the criteria,” Allamanno said.

A visit to the apartment complex easily convinced Allamanno that it was a community worth saving.

In spite of the extremely neglected condition of the concrete-block buildings — including termite damage, a failing sewage system and foundations that had been lifted by tree roots — Allamanno saw the apartment complex as a place where residents had forged strong bonds. Seniors and disabled residents knew they could rely on the young families there to run errands, and they in turn helped look out for the children.

Redding’s neighbor, Christopher Goolsby, who had lived at Norton Apartments for seven years with his wife and two young daughters, had built makeshift ramps for some of the disabled residents and helped Redding clean up after her sewage backup the best he could.

Goolsby’s elderly next door neighbor, Jritta Belk, cried at the thought of not having him around to help her.

“I don’t know what I would do if I had to move away from Chris and his family,” Belk said.

Norton Apartments is one of the few, project-based Section 8 multifamily communities remaining in Pinellas County. Families living there pay 30 percent of their annual income as rent, with the balance of the market rate being paid by HUD to the landlord.

The HUD rent subsidy is critical to prevent homelessness for families whose incomes consist of Social Security disability payments and food stamps or whose breadwinners work at low-wage jobs or are unemployed. Another group of tenants are frail elderly whose medical expenses swallow up most of their meager incomes.

Allamanno and Lee learned about the bankruptcy, which turned out to be good news. It meant that an automatic stay prevented HUD from terminating the subsidy without first asking leave of the bankruptcy court, because all executory contracts and unexpired leases remain in place when a bankruptcy is pending.

“The owner’s bankruptcy gave us the time that we needed to put together a plan to save Norton Apartments,” Allamanno said.

It was critical to secure the assistance of an attorney with bankruptcy expertise, as bankruptcy law is a complex specialty.

Kent Spuhler, executive director of Florida Legal Services, located John Lamoureux, a principal at Carlton Fields with extensive bankruptcy and construction law expertise. Lamoureux toured the property with Allamanno and met several residents.

“You see why we want to save it?” Allamanno asked.

Lamoureux gladly took the case pro bono and began crafting a strategy whereby an entity that would be approved by HUD could purchase the property out of bankruptcy by paying off the mortgage due on the property, with the approval of the bankruptcy court, and take ownership of the property free and clear.

It was an exit strategy that would benefit all of the parties involved — the owner; who would be out from under the obligation of the mortgage; the bank, who would get its mortgage paid off; HUD, who could form a future relationship with a responsible entity to manage the property and maintain the subsidy going forward; and most importantly for the Norton families, who would at last be living in renovated housing with responsible management.

But the work was far from over.

The strategy required that an entity acceptable to HUD be found to take over the property. Lee brought Norton Apartments to the attention of Frank Bowman, housing development manager for the Pinellas County Department of Community Development, which was able to secure the property through its Neighborhood Stabilization Program. In addition, Pinellas County provided a $390,000 grant from the Department of Energy to provide residents energy-star-certified ranges, refrigerators and air conditioners.

The Pinellas County Housing Authority took over ownership and management of the property, and since the closing March 15 has appointed a new full-time property manager. Contractors have begun correcting the conditions that caused Norton to fail its HUD inspections, including the long-standing sewage backup issue.

Work is set to begin on an ADA-compliant unit for Redding, pending permitting and coordination with structural work being done on other units. In the meantime, she now has a wheelchair ramp.

Allamanno points out that the story is a prime example of the saying, “It takes a village.”

She cites a long string of contributors to the process, including the Neighborhood Stabilization Grant from Pinellas County and Clearwater, the Housing Authority, the pro bono attorney from Carlton Fields, the residents themselves, and the grants from The Florida Bar Foundation that enable her and Lee to do affordable housing work.

“If any of the pieces had fallen out of the picture, those buildings would be vacant and crumbling right now instead of becoming a hub for revitalization and community services for the neighborhood,” Allamanno said.