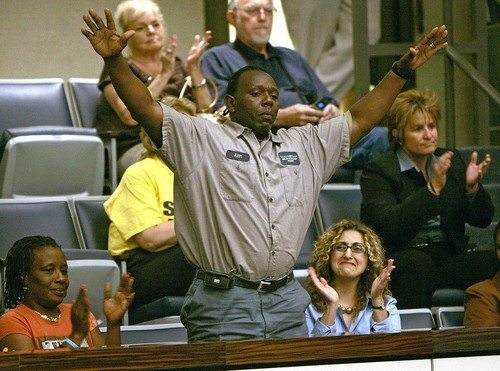

Alan Crotzer celebrates after the Florida Legislature’s passage of a bill awarding him $1.25 million in compensation for the more than 24 years he spent behind bars for a crime he did not commit.

All Alan Crotzer wanted was for someone to listen, but no one did.

Having served two years in prison for armed robbery, Crotzer had a record that made the prosecutor’s case more convincing.

He would spend more than 24 years in prison, wrongly convicted of rape, burglary, robbery and aggravated assault, and might have remained there for the rest of his life, were it not for the Innocence Project of Florida Inc.

“Nobody knew I was wrongfully convicted until they listened to me,” Crotzer said.

Mistaken identity, a misconstrued statement from a victim, botched evidence – without the help of modern crime analysis these missteps have led to wrongful convictions of Crotzer and many others for heinous crimes.

The Innocence Project of Florida Inc. has worked since 2003, using post-conviction DNA testing, to free those unjustly serving life sentences and even facing the death penalty.

They won freedom for Crotzer in 2006.

A grantee of the Foundation’s Improvements in the Administration of Justice Grant Program, the IPF has aided in the release of seven innocent prisoners, many of whom have spent more than half their lives behind bars.

The Foundation has provided nearly $900,000 to help the project accomplish its mission.

“We wouldn’t exist without The Florida Bar Foundation. They were there with us from the beginning,” said IPF Executive Director Seth Miller. “Without them there would have been an incredible void in the criminal justice community.”

Florida has had the most Death Row exonerations of any state – 26 since 1973, according to the IPF. The organization is currently working on a dozen exoneration cases and more than 100 cases that are up for review.

“Our sole mission is to find and free wrongly convicted people in Florida’s prisons,” Miller said.

After Crotzer was released, he began a hard-fought battle to receive $1.25 million in compensation from the Florida Legislature.

Along the way, he met an unlikely friend and advocate in retired Judge John Blue – the same John Blue whose signature was on a denial for DNA testing that delayed Crotzer’s exoneration.

Blue had since retired and was working at the law firm of Carlton Fields in St. Petersburg, where he began working pro bono in collaboration with the IPF on Crotzer’s claims bill to the Legislature for compensation.

“As we were going through his papers there was an order in there that one of his motions had been denied,” Blue said. “That was signed by me.”

Blue and Crotzer now joke about the meeting, but Crotzer believes it had deeper meaning.

“I looked at him and I said, ‘You denied me; now God put you in my life to get compensated,’ ” said Crotzer, who now works part time with at-risk youth at the Department of Juvenile Justice.

Blue said he wasn’t sure that he ever saw the motion, but as the chief judge at the time he got automatic credit for all the denials.

The pair has become good friends who travel together, educating young lawyers on Crotzer’s case and the importance of pro bono work.

And the two celebrated together as Blue received the Chief Justice’s Distinguished Judicial Service Award during the annual Pro Bono Awards in Tallahassee in January.

Crotzer amazes people when he tells his story and how he has forgiven those who put him in prison.

“He decided he couldn’t live with not forgiving people,” Blue said